I wrote this quickly. Apologies if it is messy or grammatically incorrect, it’s not supposed to be perfect, more an impression of a day I don’t want to forget. Also to say, my son is fine and will be fine. Thanks for reading x

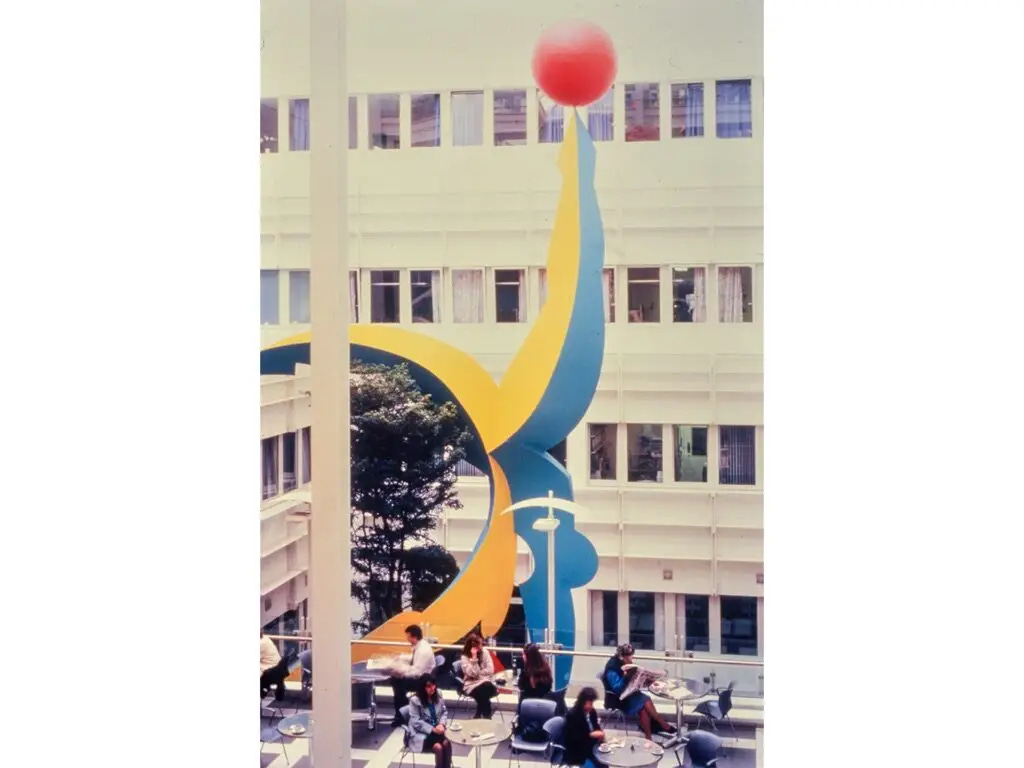

There is a piano in the hospital atrium. A man sits sideways on the stool, turned away from the keys, his eyes focussed somewhere in the middle distance, his right hand pressing down on one note over and over again. We sit in a lounge area by the coffee shop, my backpack my by feet filled with the flotsam and jetsam of our day, a drawing pad, orange peel, loose markers, an empty water bottles, chargers, our books. On the table in front of us, a ciabatta broken in two, steam rising from the hot melted cheese, a cup of tea for me, a smoothie for him and a packet of crisps. Remember when I used to call them crips. He says. He is half lying in his seat, clutching his smoothie. He looks over at a large colourful sculpture to our right. I follow his eyes. It’s a seal balancing a ball on its nose I say. Then I tilt my head, no, it’s a man doing a handstand. It’s abstract Mum, he says.

A woman walks past pushing a wheelchair with a small pallid boy covered in a blanket watching a screen fixed to the arm of the chair. We sit listening to the man playing his one note. It blends in with the other songs of this space, the low hum of the cafe’s refrigerators, the soft ping of the lift. But it feels leading too, this long line of staccato-ed sound, the underlying inevitability of its breaking and ending.

We FaceTime his grandparents: he informs them that the MRI scan was not nice. He had itchy feet. He was too hot, He couldn’t move. The noises were so loud. He doesn’t tell them about the hot tears. Palms flat on his face. I can’t stand it any more. We say goodbye and he relaxes back into his seat. I’m glad he is able to tell people about it. I want him to understand that if he’s lucky, this is what pain and discomfort will be for him; temporary things that come and go. Things he will learn to live through.

The note changes. It’s the next white note up. It feels like a release. An exhalation. It moves us into action. We gather our things, call in to the shop on the way out to buy him a chocolate bar. As he was sliding into the MRI scanner for the second time, I suggested he think about what chocolate bar he could get when it was all over. The nurse had plugged up his ears with putty to help block out the noise. He was calmer because of it. He wasn’t prepared for the noise; concentrated cold violent sound, no rhythm, no swing for his little drummer ears to grab on to, and so loud, so abrasive. He hated it. But it’s over now.

We walk back to the train station. The air is colder now, the sun receded behind clouds. Work is finishing up. The streets are busier. Our route crosses through Brompton cemetery. Let’s take our time here he says, gliding along on his scooter. A tiny grave just inside the entrance, no longer than one metre long, reads of a darling Tom who died in the 1800s at two years old. That makes me feel lucky, he says. He tells me to slow down. I’m walking too fast. He notes that on this side of the cemetery there are less big statues than on the main path we walked down on our way to the hospital. Are the people poorer here? I confirm that yes, more money buys bigger monuments and some people don’t get a gravestone at all. He ponders this for a long time. It’s not fair he says, how being poor means you can’t be remembered.

We pass a gravestone with my full name on it. This Annie died in the late 1800s. We stare at it for a while. It’s startling I say, to see my name on a gravestone like this. We move on but I’m walking too fast again. Slow down he urges. He stops and bends down to read an inscription detailing a woman who died aged forty nine. Oh mum he says that’s near your age.

Don’t worry, I tell him, I plan on living until my nineties. Then we try and work out what age he will be when I’m ninety. I do the maths out loud, get to fifty two. I wonder what you will be like when you’re fifty two I say. He says, I’m going on ahead, but you have to keep walking slowly. I watch him scoot away, mop haired, his big fluffy socks pulled up over his tracksuit bottoms. I feel a brief surge of panic, a portent of loss, hear the quiet crack of a heart breaking somewhere in the distant clouds of my future.

The train is packed. He and I sit directly opposite each other. On one side of him a heavily pregnant woman types furiously into her phone. On the other a grey haired man sleeps soundly in his seat whilst clutching his briefcase close to his chest.

He plays a video game on my phone. Occasionally he turns his eyes to glance at the pregnant woman’s phone and then goes back to his game. Without my phone I have nothing to look at so I look at him. We rumble on through West London past the backside of houses; brown brick, green patchwork gardens, the sky a fading yellow behind. We are climbing slowly through something. One note at a time.

Oh my, this was beautiful. The other day I read an article about empty nesters and burst into tears. My kids are only 5 and 7 years old.

This article made those feelings well up again.

Well done Annie, and I'm glad to hear your son is OK.

This is beautifully captured Annie, with so much just barely said, yet recognisable ❤️ That MRI noise is so savage and scary, especially for young or vulnerable ears (like my mum with dementia who found it very frightening).